Low security and its role in community safety

From time to time, you may hear reports of prisoners absconding from low security facilities.

We thought you might like some information on how prisoners are managed in low security facilities in Queensland, why low security is so important to community safety, and what happens when someone absconds.

We use the word abscond, because Queensland has not had an escape from a high security centre in 27 years (since 1998).

Low security facilities in Queensland are often commercial farms, indistinguishable from neighbouring properties, a group of houses like at Townsville Women’s Low Security, and in the case of Helana Jones Correctional Centre, a suburban house.

Prisoners building a fence at Palen Creek Correctional Centre, a low security farm in South East Queensland.

Most low security facilities also have work camps attached to them, which see prisoners living in communities across Queensland, undertaking community service and supporting the towns through natural disasters and to host significant sporting and cultural events.

Low security facilities play an important role in the rehabilitation of carefully-selected prisoners, giving them increased responsibility and the opportunity to learn vocational and life skills which reduce their risk of reoffending when released back to the community.

Security at these centres doesn’t look anything like our high security centres. These centres use dynamic security – random head counts and checks, clear rules and routines.

Women from Numinbah Correctional Centre at Warwick work camp.

Moving to low security is a privilege that prisoners have to work towards. They must have a record of good behaviour, and can not have committed serious violent crimes, or be sentenced to life in prison. They are often at the end of their sentence and soon to be released back into the community.

Providing prisoners with the opportunity prove their ability to follow rules and abide by the conditions of living in a low security setting is a valuable stepping-stone to successful rehabilitation and reintegration into the community.

A prisoner at a low security centre transforming a recycled bicycle into a wheelchair. The chairs are provided to the Lions Club, which donates them to developing countries.

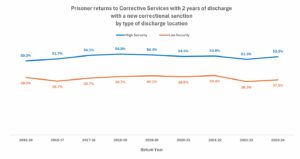

Recidivism rates amongst people who are discharged from low security show that this approach works.

They are significantly less likely to be returned to custody or get a community order in the two years following discharge compared to those who are released from high security.

Low security prisons operate on a community engagement model, where prisoners provide many hours of free labour working in communities as reparation.

In 2023-24, prisoners on the Work Camp Program completed 145,729 hours of community service equating to $4.52 million worth of labour provided to support regional Queensland.

Every year thousands of prisoners live successfully in low security environments in Queensland and in other states across Australia.

In 2023-24, 2748 prisoners were accommodated at low custody facilities and of those, only 14 individuals absconded, equating to less than 1 per cent (0.5%). All were quickly returned to high security.

In an ideal world, there would be no absconds. The reality is that absconds are not a failure of the low security model, which has proven successful over many years, but a reflection on the individuals in our custody and their decision making at that point in time.

We are constantly reassessing the security of our centres, and regularly review prisoners’ security levels and risk factors.

Abscond risks from low security facilities are managed through a thorough and ongoing assessment of prisoners to determine suitability prior to and after transfer to a low security facility.

Prisoners who abscond are recaptured, usually within a very short timeframe, and are returned to high security, losing the earned privileges of low security and potentially facing an additional sentence.

Corrections is not simply about infrastructure and punitive incarceration. It is at its heart a human business, and occasionally, despite the best efforts of our officers, the people in our custody and care make bad decisions.

It is our job to hold individuals accountable for their decisions, model positive behaviour and support them to become better members of society.